A professional development program to improve community care professionals’ confidence and give them tools to support people who are pregnant or postpartum and living with a substance use disorder.

Background

VisitBoost offers a technology- based solution to reach community care professionals, including home visitors, toward the goal of reducing stigmatization and improving uptake of health services for people with SUD during pregnancy and postpartum. VisitBoost holds promise to reduce stigma during pregnancy and postpartum to support and improve the use of best practices to ultimately support long-term benefits for caregivers and their child(ren).8

Program Overview

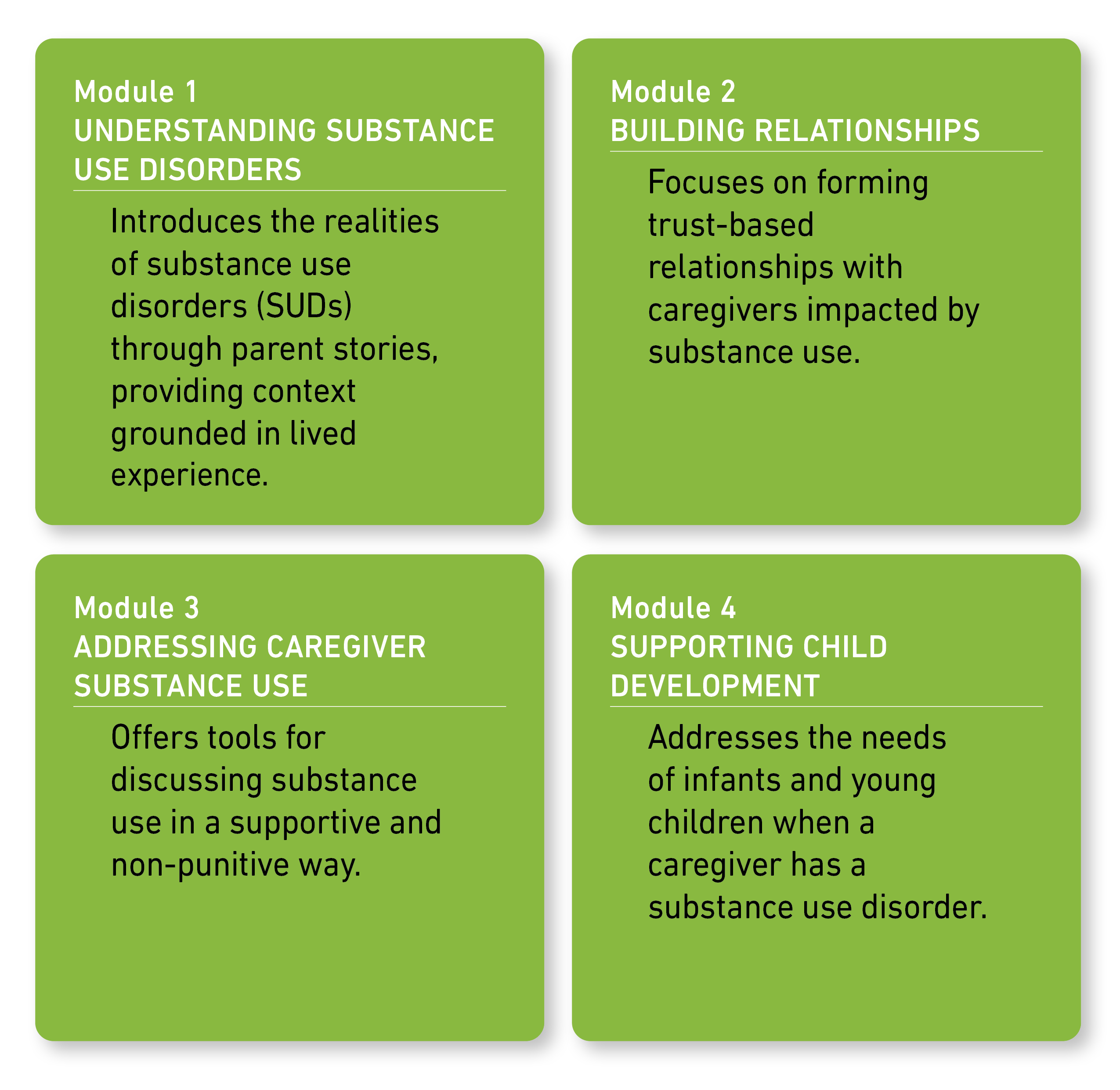

VisitBoost is a 4-module training program for community care professionals working with families impacted by substance use disorders during pregnancy and postpartum. It is designed to support destigmatized care and increase knowledge of best practices.

Feasibility Study

1. Formative Work

We collaborated with a community advisory board and home visitor advisory board throughout an iterative program development process to ensure the program is responsive to the needs of families and home visitors working in the field.

2. Clinical Trial

We completed a feasibility study with 52 home- visiting professionals. All participants received access to the VisitBoost program and completed surveys at baseline and 4 weeks later. Our pre-post feasibility study observed significant improvements across all measured outcomes.

3. Key Findings

Initial efficacy

- There was strong evidence of initial efficacy, with increases in knowledge, practice intentions, and self-efficacy ratings, and a reduction in stigma.

DEFINITIONS

Knowledge: Knowledge of access to medical care, treatments, and services for people impacted by substance use disorders.

Practice intentions: Intention to practice services and care for caregivers affected by substance use.

Self-efficacy: Confidence to support caregivers impacted by substance use disorder.

Stigma: Experiences and beliefs about people who use drugs.

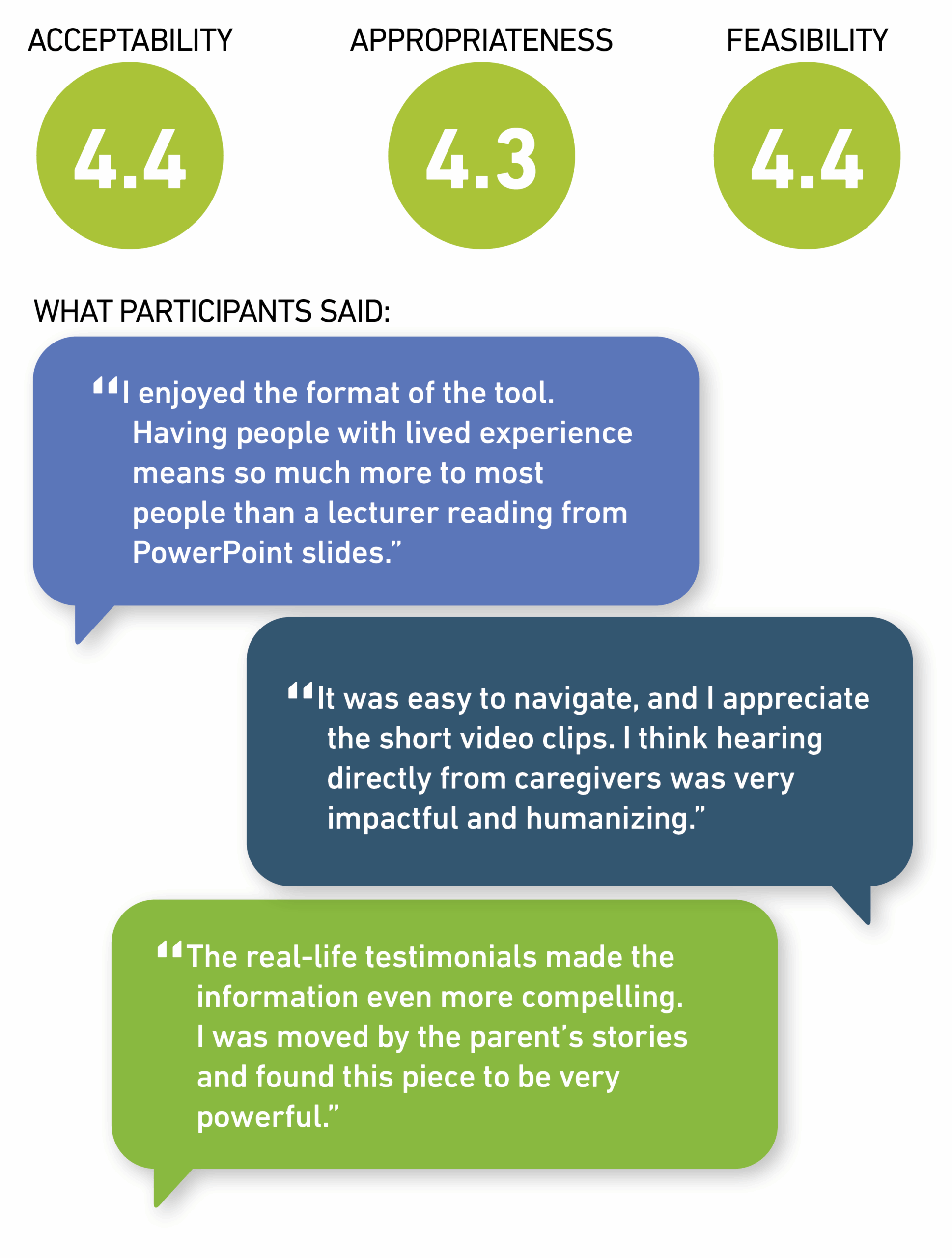

- High acceptability and feasibility ratings

On a 5-point scale, participants rated VisitBoost highly.

4. What This Means

VisitBoost demonstrates promise as an effective professional development intervention for home visitors. The findings from this feasibility study indicate that participants not only learned from the program, but also felt more confident and motivated to implement best practices in their work with families impacted by substance use disorders.

References

2 Miler JA, Carver H, Foster R, Parkes T. Provision of peer support at the intersection of homelessness and problem substance use services: a systematic “state of the art” review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):641. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8407-4

3 Tracy K, Wallace SP. Benefits of peer support groups in the treatment of addiction. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:143-154. doi:10.2147/SAR.S81535

4 Winhusen T, Wilder C, Kropp F, Theobald J, Lyons MS, Lewis D. A brief telephone-delivered peer intervention to encourage enrollment in medication for opioid use disorder in individuals surviving an opioid overdose: Results from a randomized pilot trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216:108270. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108270

5 John McConnell K, Kaufman MR, Grunditz JI, et al. Project Nurture Integrates Care And Services To Improve Outcomes For Opioid- Dependent Mothers And Their Children. Health Aff. 2020;39(4):595- 602. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01574

6 Terplan M, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Chisolm MS. Prenatal Substance Use: Exploring Assumptions of Maternal Unfitness. Subst Abuse. 2015;9(Suppl 2):1-4.

7 Ecker J, Abuhamad A, Hill W, et al. Substance use disorders in pregnancy: clinical, ethical, and research imperatives of opioid epidemic: A report of a joint workshop of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and Amer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(1):B5-B28. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.022

8 Roberts SCM, Pies C. Complex calculations: how drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(3):333-341. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0594-7

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number R43DA057785. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.